About

Donald Greenhaus

From Photojournalism to Abstract Expressionism and Then Some…

Greenhaus did it all, and he did it with a camera.

From Photojournalism to Abstract Expressionism and Then Some…

Greenhaus did it all, and he did it with a camera.

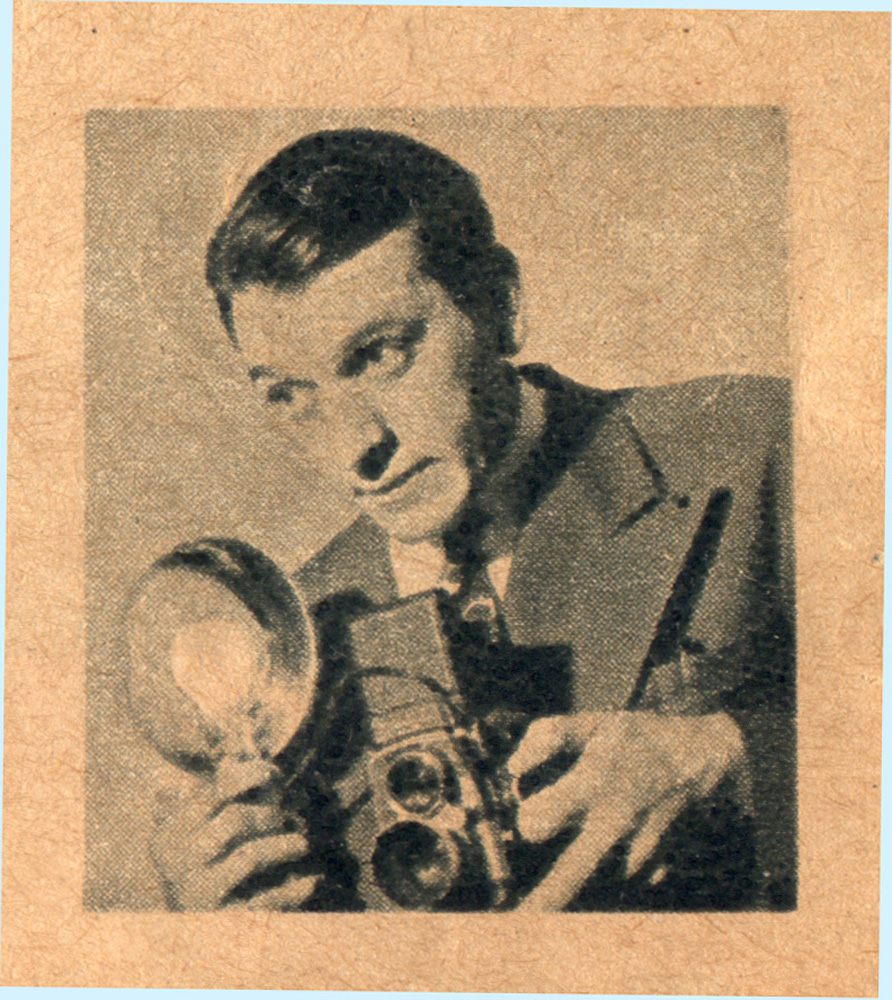

I got into photography chasing a ghost – my father’s. My initial love of photography came from him and his love for photography. When my father died, they had a hard time deciding what to put on his gravestone. My brother Edwin said, “He loved his camera. Why don’t we put that on it.” So my mother had a Speed Graphic carved on my father’s gravestone.

I actually don’t know how early I began. I do know that I was four years old and I started drawing and painting. Anyone wanting me would know to follow the crayon marks on the walls and furniture until they found me covered with color, happily lost in my reverie. When I was nine years old, my father died. He was 42 years old. He was a photographer with The New York Times. His last camera was my first camera, but it will always be “my father’s camera”. I picked up his camera (an old 4×5 Speed Graphic with a broken range finder), stopped drawing, and started making photographs. From the very beginning, it was the most exciting experience I had ever felt, both scary and exhilarating at the same time.

My driving force was a combination of love and rage. As the years went by, the rage was replaced by sadness. Most of my early work and life speak of these things. Of the human condition, of the nobility of the human spirit. Now the sadness has been replaced by joy and the darkness transformed into light. I ran as fast and as hard as I could – sometimes from, other times to. Most times not knowing where. But always making photographs.

My work still speaks of the human condition, only this time I’m speaking about me – my human condition. No matter what else I was working on or doing, it seemed as if I was always doing my photographs, seeing my life through my own eyes. Eyes that have a particular vision, a vision that uses colors from the palette of my own sensibilities, thoughts and emotions – sometimes fear, sometimes ecstasy, sometimes who knows what. My photographs are about my feelings, from living my life and seeing my world as if I were running past it in a dream, walking down the street so spaced out not knowing whether it’s night or day, looking at something so hard and so long that I didn’t see it anymore, standing in the sun and feeling the warmth of the sun all over me. I am seeing my feelings and my thoughts outside of myself.

For the last 30 years or so my work has been thousands of rolls of film sitting in shoe boxes stashed all around my loft. Every once in a while I would develop a roll or two, make a print, go back to my other work. Finally, in 1996, I developed the film and rebuilt my darkroom, and I’m now starting to print these negatives. This is an ongoing process – shooting, developing, printing, and building. I have hundreds of thousands of negatives and every day I’m making more. Being an artist is a way of life. A way of being – being alive. I am working on something I call “Conversations With Trane” – exchanges that are ongoing between John Coltrane’s music and me. Also another piece I call “Prayers”.

I turned 63 years old in December 2004 and I’ve been making photographs for 55 years. I’m still learning and growing. My work is because I am, and that’s what it’s about – a celebration of life. When I was a kid and I made my first photograph, I got so excited my feet didn’t touch the ground for days. Now my love, passion, understanding, and commitment are stronger and more exciting than ever. My work is my statement. I wake up each morning very grateful that I have another day to do my work.

“I Look into the Mirror and See My Father’s Face”

My father died in May of 1951. He was 42 and I was 9 years old. I speak more with him now than before he died.

I knew my father was not there anymore, but I didn’t know why. The only knowledge of him that I had growing up was his photographs – his camera and other peoples’ memories.

The last year of my father’s life, he was a room that I had to walk quietly past. He went into the hospital and I never saw him again. And then his room became my room. My first camera was his last camera but will always be “my father’s camera.” I have no memories of my father. I don’t remember if we ever walked together or laughed or cried together. I know that he loved photography.

When I was 50, I had a dream – l dreamt that there was a baby in a playpen. A pair of arms came down from the sky and picked up the baby, hugged him and swung the baby around and around. The baby (arms and legs waving and kicking) was laughing and giggling and screaming with joy. At first I thought the arms were God’s arms. I knew the baby was me, but then I looked up and instead of God, I saw my father’s face. I know he loved me.

I forgive my father for dying.

I forgive myself for thinking that he abandoned me.

I spent a lot of years being angry and feeling lost. I found myself, and in finding myself, I found my father. I spent a lot of years regretting that I didn’t know him and he didn’t know me. Blocking out whatever memory that I had of him because it was too painful – Trying to separate myself from him and him from me – Finding out where he ended and I began – Denying each from the other. ln blocking out the pain, I blocked out the good as well. I spent so many years of my life blocking out, fighting the pain and trauma of his death, that I didn’t see anything else.

I know that it doesn’t matter anymore. Now instead of the pain I choose to feel only the joy. My father – not his death – was and is a great and constant inspiration for me. I’ve had him with me all these years and l just realized it. He’s always with me. We walk and talk and cry and laugh together.

Above: Ben Greenhaus

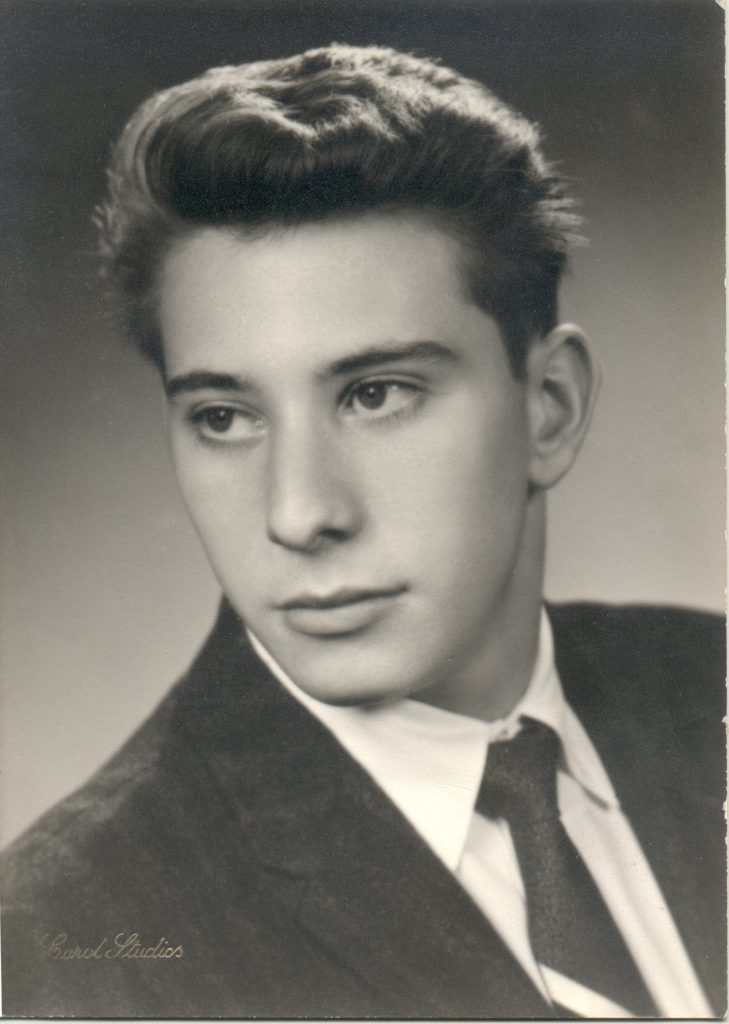

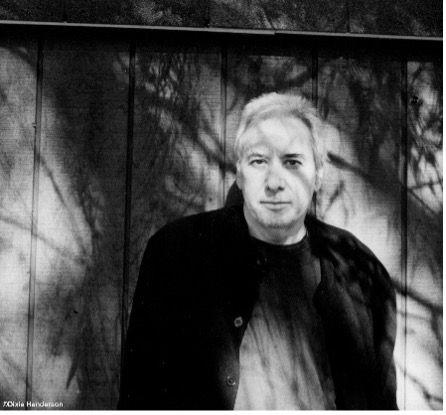

Above: Donald Greenhaus

We live in a perverse world. There are people who don’t have a place to sleep – and we have people who build luxury buildings that are too tall. I was amazed to find out that it cost 12 million dollars to tear down 10 stories of a luxury building, but you can’t afford to build low income housing.

We have people who are hungry – and we pay farmers not to produce food. We have people who don’t have a way to keep warm in winter – and we have people running for president of this country who complain that they are only getting contributions of 300 thousand dollars a week to support their campaign, and it’s not enough to win.

We have whole countries in other parts of the world that are dying – and we have people here who are able to pay 100 million dollars to keep out of jail (the only real crime is getting caught).

Everyday we are bombarded with offers of something for nothing, pandering to what the system considers to be mankind’s real god – MONEY. “Buy a magazine and get a chance to win 10 million dollars.”

We are living in the Age of the Spiritually Impoverished. We have generations of students graduating from our schools who can’t read or write – if the battery in their computer goes, they can’t add either. They are overfed and under nourished and all they want to do is sell out before they have anything to sell.

We are living in a time of built-in obsolescence. Most things are made to last as long as the payments last, and the only thing mankind has made that will last longer than a lifetime is a cloud of nuclear waste that will last for 25 thousand years.

Our most precious natural resource – HUMANITY – is being pissed away. More and more there is no place for our old people. More and more our young people are being destroyed before they get a chance to become old.

I refuse to believe that the human condition has to be so inhuman.

I would like to thank Alexis Gadsden of Pride Site, Fred Siegal of Respite House, Bob Meltzre of The Educational Alliance, and especially Marion Lazer for enabling us in the show to help, in a small way, our fellow human beings.

I would like to dedicate this show to the children who danced in front of our paintings with the wish that by the time they get old, the world will have become more humane.

Written for “Artists’ Benefit for the Homeless”

Speech by Donald Greenhaus – February 28, 1988

The Educational Alliance Gallery, NYC, February 22 – March 18, 1988

Donald Greenhaus was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1941 and grew up on Long Island. His father, Ben Greenhaus, a photographer with The New York Times, died in 1951 at the age of 42. Donald was nine years old. He picked up his father’s camera and started taking photographs.

Throughout the 50s Greenhaus worked at a myriad of after school, weekend and finally full time photography jobs. From 1963 through 1966 he worked for Metropolitan Photo Service, a photo agency that was located in the old Palace Theater Building on 47th Street and Broadway. They were the official photographers for most of the movie companies in New York City and Greenhaus took photographs of not only show business but society and political personalities, as well.

In 1966 Greenhaus opened his own commercial photography studio at 1234 Broadway. By 1968 Greenhaus realized that he knew a lot about photography but not a lot about life. He decided to stop shooting photographs for other people and start shooting just for himself. He moved to a loft on Greene Street in Soho where he lived until his death. The world was changing and so was Greenhaus. The human condition became the focus of his interest.

Instead of shooting photographs of things that people wanted to see, he started shooting photographs of things that they didn’t want to see, the dark side of life – photo essays about old age in a nursing home, junkies, alcoholics, male strip houses, prostitutes – culminating with what Greenhaus didn’t want to see – an embalming and an autopsy. To quote Greenhaus about his early work – “There was a war going on in the United States that had to be fought. The war of racism, of hunger and poverty, of being old in a society that worships youth but destroys its young. A war of saving face but not humanity. Little has value and everything costs too much.” Greenhaus believed the human condition. It didn’t have to be so inhuman.

In 1974 Greenhaus became a casualty of the “dark side”. He couldn’t look anymore. All he saw was pain, fear and suffering. Others, and ultimately his own. He stopped shooting photographs of people. For a while, he stopped shooting photographs. When he began to work again, his work became the journey of his life, from that darkness into light.

Greenhaus’ work and name began to appear in magazines, newspapers, galleries and museums both in the United States and abroad. He began to make etchings, lithographs and silkscreens from his photographs and started painting, as well. This work also found its way into exhibitions and museum collections. He wrote about photography for Arts Magazine. He lectured, gave workshops and was a visiting artist in residence at numerous colleges around the country. Greenhaus was on the faculty of The New School for Social Research for thriteen

(13) years. He also taught in prisons, drug programs in Harlem and alternative high schools in the Bronx, as well as privately being a mentor to a few people – including Magnum photographer Eli Reed.

“Nighttime,” “Daytime”and“In Between Time” make up a trilogy of photographs from the 70s through the 90s documenting that journey from the early darkness to the shimmering present work that is so full of light. Greenhaus’ work is a thorough blending of his vision of reality with his fantasies, thoughts and feelings. They are the beginnings of Greenhaus’ study of light and flatness and three dimensionality in a photograph.

In 1993, Greenhaus was one of 25 world class photographers from around the globe invited by Fundacion Cultural Banesto of Spain to participate in a project to photograph the major cities of Spain. Each photographer was specifically chosen for their personal vision in order to give the project a multi-faceted flavor. Greenhaus’ images from Spain are published in magazines and books. His gelatin silver prints from the project are in the permanent collections of Fundacion Cultural Banesto and Museo National Centro de Arte Reina Sofia.

In 2000, Greenhaus began a new trilogy – starting with “Conversations (with Trane)” – exchanges between John Coltrane’s music and Greenhaus’ photographs. These images are most like jazz improvisations in their pure spontenaity. In some respects, it is very much like the “call and answer” of gospel music, or the collective coherent thinking and feeling in a jazz improvisation. Greenhaus allows the idea to express itself in communication with his camera, hands and feelings in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere with capturing something that is experienced rather than merely seen or heard by Greenhaus and through Greenhaus by the viewer. He worked on the second part, started in 2003. He called “Prayers”. Greenhaus was always creating new and different ways of seeing and expressing the photographic image.

Ultimately, Greenhaus was about the human condition, and the strength and resilience of the human spirit. Greenhaus’ photographs are a vision and a celebration of his passion for life – they came from his very soul.

Shabobba® International, LLC.

1-816-746-7830

P.O.Box 29245

Kansas City, Missouri 64152 USA

info@shabobba.com

Legalized Notice: No part of this website or any of the images may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, computer recording or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed without written permission from Dixie Henderson, Shabobba® International, LLC.

Attention Website Visitor: Should you see Donald Greenhaus’ works of art/photography elsewhere, please ask yourself, “Is this legal?” Shabobba ® International, LLC is the only legal seller of Donald Greenhaus’ work – worldwide.

Website Design by Jake Parrott Creative

Shabobba® International, LLC.

1-816-746-7830

P.O.Box 29245

Kansas City, Missouri 64152 USA

info@shabobba.com

Fill out the form below, and we will be in touch shortly.

If interested, we invite Donald’s students to contact Shabobba® for a possible interview for an upcoming publication.